This step is going to be the most complicated, but if you can get through and understand this, then the rest is going to be a piece of cake. We currently are able to use our Lexer to get an array of Tokens. We now wish to parse the tokens into an AST (Abstract Syntax Tree). It gets this name due to the tree-like structure it produces when fully parsed. Every literal, expression, block, return, if, while, def, (any syntactic component of the language) is going to have its own node. Each of these nodes will reference other nodes to indicate how they are related to one another.

For instance, the binary operation 2 + 2 could be looked at as a binary expression node, with an operator node represented by the plus symbol, and a left hand side and right hand side expressions that are each in this case simply a number literal of 2. In this example the binary operator expression node would be considered the root, while the remaining nodes are its children. This tree like structure is very important as it makes our code-generation stage much more simple. In order to translate the AST into LLVM IR we simply will walk the AST, inspecting nodes as we go, and calling the LLVM IR Builder api with references to the respective child nodes.

BinaryExpressionNode -> 2 + 2

Operator -> +

LHS -> 2

RHS -> 2

In order to create our AST we are going to need a class for each node type so as to allow each node to have instance variables that reflect the required child nodes for each node type that LLVM understands and that we wish to port into our language. Initially we only need a few node types, and all our code will be treated as though its being called from the main function and therefore appended to the end of the main function's BasicBlock as we go. Once we are ready to add control flow, loops, and functions we will need to keep track of the blocks in our program and append to the correct one during code generation. Finally we will implement the puts command as a language built-in which will require some special parsing and code generation logic to accommodate its features. A language built-in means that rather than forcing a user to implement a function and compile it each time with their own code, the language will have the function signature and implementation pre-compiled in the standard library so that every program linked against the standard library will have the same desired implementation of said function.

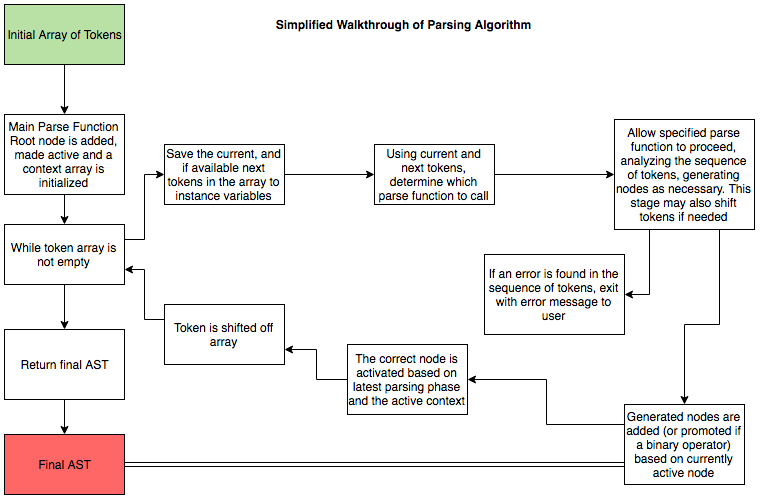

Our parser will work by inspecting the current token in the array. The parser will be aware of each node type and how it relates to other node types in sequence. Each line will be treated as an expression, of which itself may consist of multiple other expressions. The parser will determine which tokens should be expected following a given token, if those tokens are not found, an error will be generated to help the user determine where a syntax error is occurring. Otherwise the parser will continue to take the tokens and generate the required node structure to form the final AST. We should be able to easily inspect our AST at the end of this stage to visually debug and ensure our code-generation calls are getting the correct information.

If we use our initial example code from chapter 0.

# I am a comment!

four = 2 + 2

puts four

puts 10 < 6

puts 11 != 10We will be parsing this into an AST that will look something like this.

Expressions Node : [four = 2 + 2, puts four, puts 10 < 6, puts 11 != 10]

[0]

|-> Variable Declaration Node : four = 2 + 2

|---> Binary Expression Node : 2 + 2

|-----> Number Literal : 2

|-----> Number Literal : 2

[1]

|-> Call Expression Node : puts four

|---> Declaration Reference Expression : four

[2]

|-> Call Expression Node : puts 10 < 6

|---> Binary Expression Node : 10 < 6

|-----> Number Literal : 10

|-----> Number Literal : 6

[3]

|-> Call Expression Node : puts 11 != 10

|---> Binary Expression Node : 11 != 10

|-----> Number Literal : 11

|-----> Number Literal : 10

Something that may be of use to you for experimental purposes is to see Clang's AST representation for simple C code. This is useful as LLVM uses Clang's AST in its own codegen methods and should be informative to browse. Below is a simple C code example.

// example_clang/main.c

int addFour(int x) {

return x + 4;

}

int main(){

int four = addFour(0);

}clang -cc1 -ast-dump name_of_file.cIf we scrape out some of the extraneous information we can see Clang's AST for this code:

|-FunctionDecl 0x7f9247882400 <main.c:1:1, line:3:1> line:1:5 used addFour 'int (int)'

| |-ParmVarDecl 0x7f92478316d8 <col:13, col:17> col:17 used x 'int'

| `-CompoundStmt 0x7f9247882590 <col:20, line:3:1>

| `-ReturnStmt 0x7f9247882578 <line:2:2, col:13>

| `-BinaryOperator 0x7f9247882550 <col:9, col:13> 'int' '+'

| |-ImplicitCastExpr 0x7f9247882538 <col:9> 'int' <LValueToRValue>

| | `-DeclRefExpr 0x7f92478824f0 <col:9> 'int' lvalue ParmVar 0x7f92478316d8 'x' 'int'

| `-IntegerLiteral 0x7f9247882518 <col:13> 'int' 4

`-FunctionDecl 0x7f92478825f8 <line:6:1, line:8:1> line:6:5 main 'int ()'

`-CompoundStmt 0x7f92478827e8 <col:11, line:8:1>

`-DeclStmt 0x7f92478827d0 <line:7:2, col:23>

`-VarDecl 0x7f92478826b0 <col:2, col:22> col:6 four 'int' cinit

`-CallExpr 0x7f92478827a0 <col:13, col:22> 'int'

|-ImplicitCastExpr 0x7f9247882788 <col:13> 'int (*)(int)' <FunctionToPointerDecay>

| `-DeclRefExpr 0x7f9247882710 <col:13> 'int (int)' Function 0x7f9247882400 'addFour' 'int (int)'

`-IntegerLiteral 0x7f9247882738 <col:21> 'int' 0

Our parser is going to parse binary operations by taking a somewhat novel yet simple approach. In basic terms, when our parser reaches an expression, it will append the number literal nodes and make it the active node in anticipation of an impending binary node. If a binary node is reached, it then seeks the suitable insertion point in the AST and then promotes itself to that node, assuming that nodes children, itself becoming the new active node in the parse tree.

If you are like me the above words might sound pretty confusing so a picture is worth a 1000 words:

watch as it parses the expression 2 * 5 + 3 in sequence

step 1 Expression node is added with first token value - literal value 2 active

Root Node

Expression Node

Literal Node 2 (Active)

step 2 A binary operator is reached, promoted, inherits literal as its child, and is now the active node

Root Node

Expression Node

Operator Node * (Active)

Literal Node 2

step 3 Next literal is appended to active node and then itself becomes active

Root Node

Expression Node

Operator Node *

Literal Node 2

Literal Node 5 (Active)

step 4 New operator is reached, is lower precedence than * operator so is therefore promoted twice, and is new active node

Root Node

Expression Node

Operator Node + (Active)

Operator Node *

Literal Node 2

Literal Node 5

step 5 Final token is reached and appended to active node, resolving expression AST

Root Node

Expression Node

Operator Node +

Literal Node 3

Operator Node *

Literal Node 2

Literal Node 5

parsing : 2 * 3 + (4 * (5 + 6) * 7) + 8 * 9

Root

Expression Node

Operator Node +

Operator Node +

Expression Node (4 * (5 + 6) * 7)

Operator Node *

Operator Node *

Expression Node (5 + 6)

Operator Node 5

Literal Node 5

Literal Node 6

Literal Node 7

Literal Node 4

Operator Node *

Literal Node 8

Literal Node 9

Operator Node *

Literal Node 2

Literal Node 3

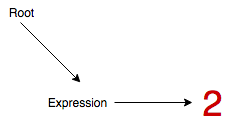

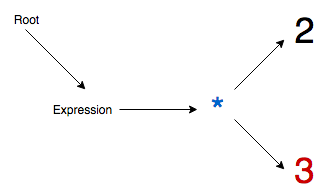

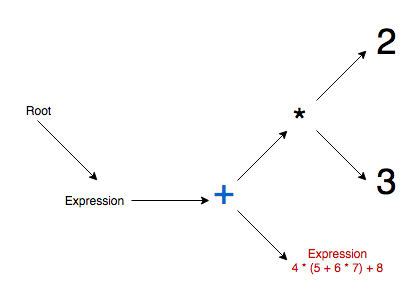

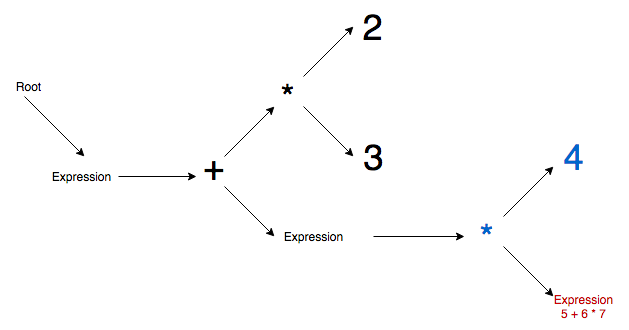

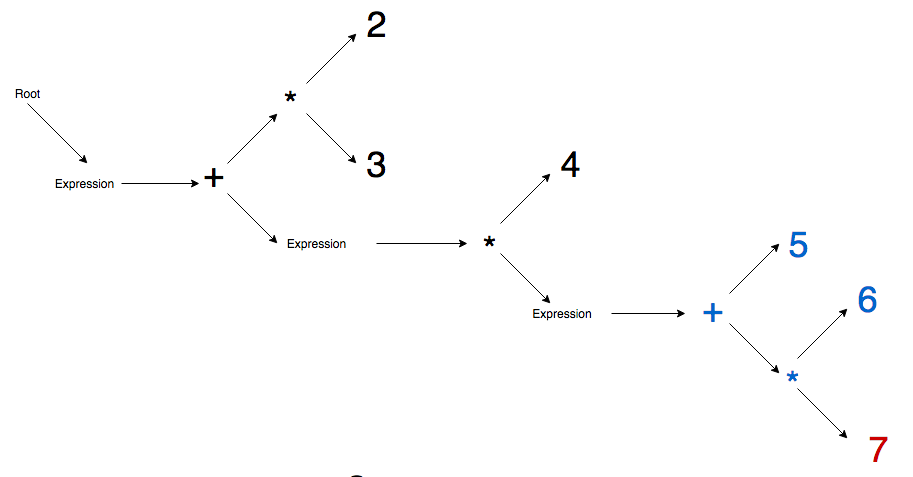

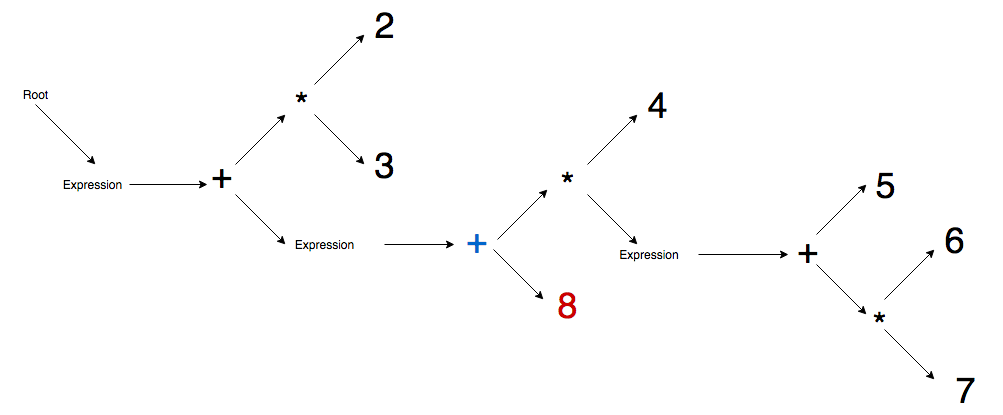

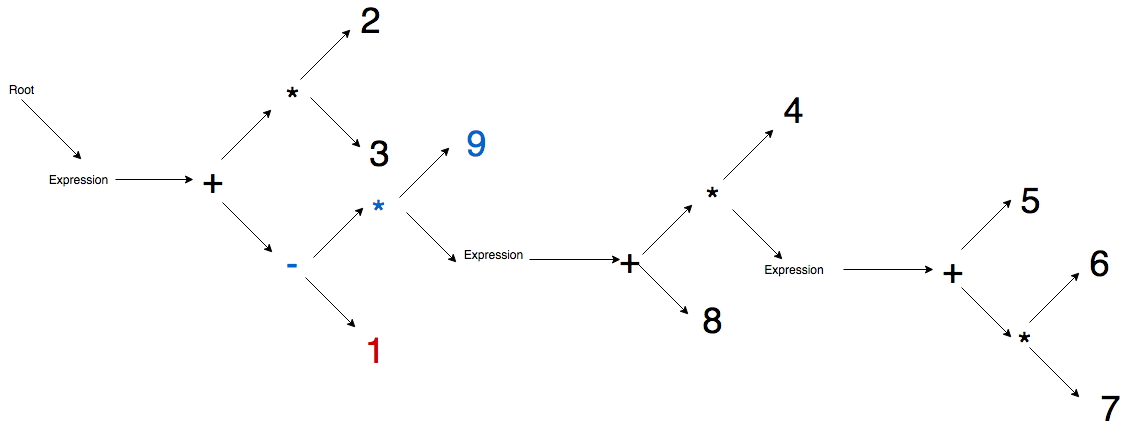

Here are some sketches of this process to help you visualize.

Blue means this node is new this step, red means it is both new and currently active.

In this example we are using the expression:

2 * 3 + (4 * (5 + 6 * 7) + 8) * 9 - 1Step 1 - Root node and main expression node generated.

Step 2 - Begin parsing main expression, append 2 literal node.

Step 3 - Multiplication operator is promoted, and literal 3 appended to it.

Step 4 - Addition operator is promoted to top, the multiply operator becomes its child, and the parenthesis expression is also appended as its child

Step 5 - First 4 literal is appended to expression node, then multiplication operator is promoted, and then expression node is appended to multiplication node as active node.

Step 6 - Inner parenthesis expression is parsed, 5 literal to expression node, addition is promoted, 6 literal to addition node, multiplication is promoted, 7 literal to multiplication node.

Step 7 - First parenthesis closes so active node jumps to closest expression node parent and then immediately promotes addition binary and appends 8 literal as its child.

Step 8 - Second parenthesis closes so active node jumps to closest expression node parent and then immediately promotes multiplication, appends literal 9 to multiplication, double promotes subtraction, and then finally appends 1 literal to subtraction node.

Visualize how the active node is changing as it parses the expressions and inner expressions.

The above approach allows us to parse each token in sequence and handle parenthesis scope because the following is true:

- Expression nodes act as gatekeepers, preventing operators from promotion beyond their borders.

- Expression nodes act as beacons, allowing the closing parenthesis to correctly activate the next required node in the parsing process.

- promote and add_child in accordance with the active node should always resolve to the correct place if there are no syntax errors.

- We likely can test for these syntax errors and provide user friendly messages if this situation is detected.

The algorithm can be simply stated as follows:

Whenever a opening parenthesis is encountered,

the active node appends an expression node

which then becomes the new active node

Whenever a closing parenthesis is encountered,

the active node is recursively changed to its own parent node

until the active node is an expression node.

This process provides the boundary for the operator nodes

and the designation for the active node once resolved.

Here is a high level view of what the parser is doing to generate the AST from a given array of tokens.